An IBM Quantum Computer Will Soon Pass the 1,000-Qubit Mark – IEEE Spectrum

IEEE websites place cookies on your device to give you the best user experience. By using our websites, you agree to the placement of these cookies. To learn more, read our Privacy Policy.

The Condor processor is just one quantum-computing advance slated for 2023

A researcher at IBM’s Thomas J. Watson Research Center examines some of the quantum hardware being constructed there.

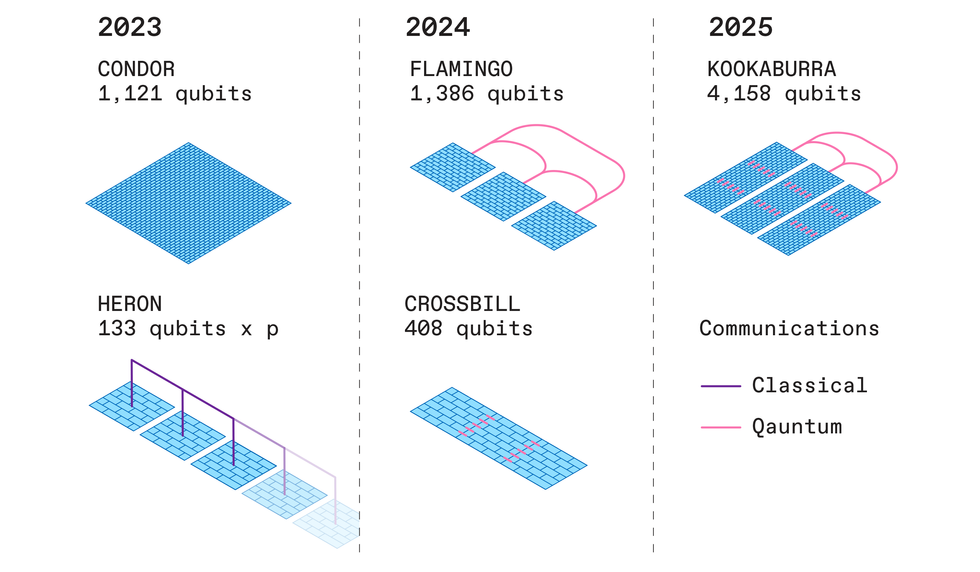

IBM’s Condor, the world’s first universal quantum computer with more than 1,000 qubits, is set to debut in 2023. The year is also expected to see IBM launch Heron, the first of a new flock of modular quantum processors that the company says may help it produce quantum computers with more than 4,000 qubits by 2025.

While quantum computers can, in theory, quickly find answers to problems that classical computers would take eons to solve, today’s quantum hardware is still short on qubits, limiting its usefulness. Entanglement and other quantum states necessary for quantum computation are infamously fragile, being susceptible to heat and other disturbances, which makes scaling up the number of qubits a huge technical challenge.

Nevertheless, IBM has steadily increased its qubit numbers. In 2016, it put the first quantum computer in the cloud anyone to experiment with—a device with 5 qubits, each a superconducting circuit cooled to near absolute zero. In 2019, the company created the 27-qubit Falcon; in 2020, the 65-qubit Hummingbird; in 2021, the 127-qubit Eagle, the first quantum processor with more than 100 qubits; and in 2022, the 433-qubit Osprey.

Other quantum computers have more qubits than does IBM’s 1,121-qubit Condor processor—for instance, D-Wave Systems unveiled a 5,000-qubit system in 2020. But D-Wave’s computers are specialized machines for solving optimization problems, whereas Condor will be the world’s largest general-purpose quantum processor.

“A thousand qubits really pushes the envelope in terms of what we can really integrate,” says Jerry Chow, IBM’s director of quantum infrastructure. By separating the wires and other components needed for readout and control onto their own layers, a strategy that began with Eagle, the researchers say they can better protect qubits from disruption and incorporate larger numbers of them. “As we scale upwards, we’re learning design rules like ‘This can go over this; this can’t go over this; this space can be used for this task,’” Chow says.

Other quantum computers with more qubits exist, but Condor will be the world’s largest general-purpose quantum processor.

With only 133 qubits, Heron, the other quantum processor IBM plans for 2023, may seem modest compared with Condor. But IBM says its upgraded architecture and modular design herald a new strategy for developing powerful quantum computers. Whereas Condor uses a fixed-coupling architecture to connect its qubits, Heron will use a tunable-coupling architecture, which adds Josephson junctions between the superconducting loops that carry the qubits. This strategy reduces crosstalk between qubits, boosting processing speed and reducing errors. (Google is already using such an architecture with its 53-qubit Sycamore processor.)

In addition, Heron processors are designed for real-time classical communication with one another. The classical nature of these links means their qubits cannot entangle across Heron chips for the kind of boosts in computing power for which quantum processors are known. Still, these classical links enable “circuit knitting” techniques in which quantum computers can get assistance from classical computers.

For example, using a technique known as “entanglement forging,” IBM researchers found they could simulate quantum systems such as molecules using only half as many qubits as is typically needed. This approach divides a quantum system into two halves, models each half separately on a quantum computer, and then uses classical computing to calculate the entanglement between both halves and knit the models together.

IBM Quantum State of the Union 2022

While these classical links between processors are helpful, IBM intends eventually to replace them. In 2024, the company aims to launch Crossbill, a 408-qubit processor made from three microchips coupled together by short-range quantum communication links, and Flamingo, a 462-qubit module it plans on uniting by roughly 1-meter-long quantum communication links into a 1,386-qubit system. If these experiments in connectivity succeed, IBM aims to unveil its 1,386-qubit Kookaburra module in 2025, with short- and long-range quantum communication links combining three such modules into a 4,158-qubit system.

IBM’s methodical strategy of “aiming at step-by-step improvements is very reasonable, and it will likely lead to success over the long term,” says Franco Nori, chief scientist at the Theoretical Quantum Physics Laboratory at the Riken research institute in Japan.

In 2023, IBM also plans to improve its core software to help developers use quantum and classical computing in unison over the cloud. “We’re laying the groundwork for what a quantum-centric supercomputer looks like,” Chow says. “We don’t see quantum processors as fully integrated but as loosely aggregated.” This kind of framework will grant the flexibility needed to accommodate the constant upgrades that quantum hardware and software will likely experience, he explains.

In 2023, IBM plans to begin prototyping quantum software applications. By 2025, the company expects to introduce such applications in machine learning, optimization problems, the natural sciences, and beyond.

Researchers hope ultimately to use quantum error correction to compensate for the mistakes quantum processors are prone to make. These schemes spread quantum data across redundant qubits, requiring multiple physical qubits for each single useful logical qubit. Instead, IBM plans to incorporate error-mitigation schemes into its platform starting in 2024, to prevent these mistakes in the first place. But even if wrangling errors ends up demanding many more qubits, IBM should be in a good position with the likes of its 1,121-qubit Condor.

Charles Q. Choi is a science reporter who contributes regularly to IEEE Spectrum. He has written for Scientific American, The New York Times, Wired, and Science, among others.

The Commodordion is played just like a traditional instrument

Like a traditional accordion, the Commodordion can be played by squeezing the bellows and pressing keys, but in addition, it has sequencer features.

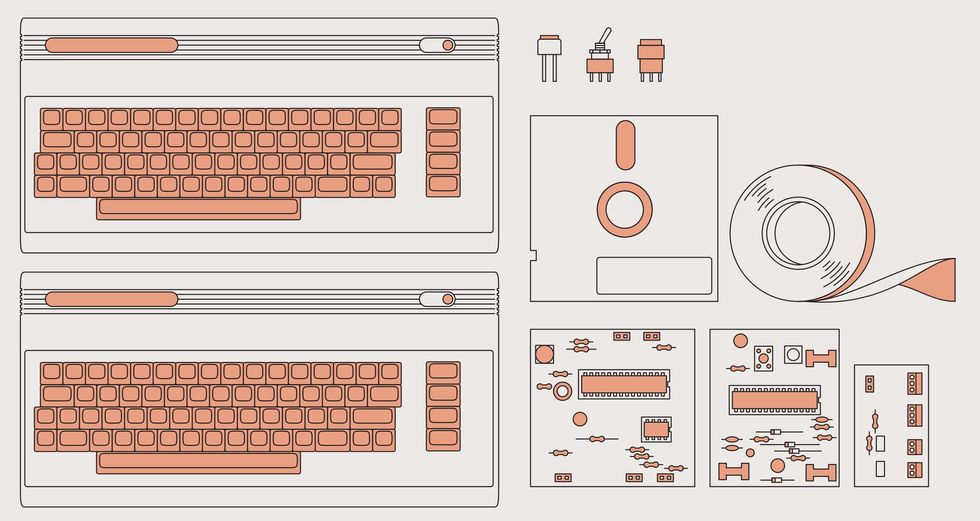

Accordions come in many shapes. Some have a little piano keyboard while others have a grid of black and white buttons set roughly in the shape of a parallelogram. I’ve been fascinated by this “chromatic-button” layout for a long time. I realized that the buttons are staggered just like the keys on a typewriter, and this insight somehow turned into a blurry vision of an accordion built from a pair of 1980s home computers—these machines typically sported a built-in keyboard in a case big enough to form the two ends of an accordion. The idea was intriguing—but would it really work?

I’m an experienced Commodore 64 programmer, so it was an obvious choice for me to use that machine for the accordion ends. As a retrocomputing enthusiast, I wanted to use vintage C64s with minimal modifications rather than, say, gutting the computer cases and putting modern equipment inside.

As for what would go between the ends, accordion bellows are a set of semi-rigid sheets, typically rectangular with an opening in the middle. The sheets are attached to each other alternating between the inner and outer edges. Another flash of insight: The bellows could be made from a stack of 5.25-inch floppy disks.

Now I had several compelling ideas that seemed to work together. I secured a large quantity of bad floppies from a fellow C64 enthusiast. And then, armed with everything I needed and eager to start, I was promptly distracted by other projects.

Some of these projects involved ways of playing music live on C64 computers. The idea to model a musical keyboard layout after the chromatic-button accordion became a standalone C64 program released to the public called Qwertuoso.

That could well have been the end of it, but I had all these disks on my hands, so I decided to go ahead and try to craft a bellows after all. The body of a floppy disk is made from a folded sheet of plastic, which I unfolded to form the bellow’s segments. But I had underestimated the problem of air leakage. While the floppy-disk material is airtight, the seams aren’t. In the end I had to patch the whole thing up with multiple layers of tape to get the air to stay inside.

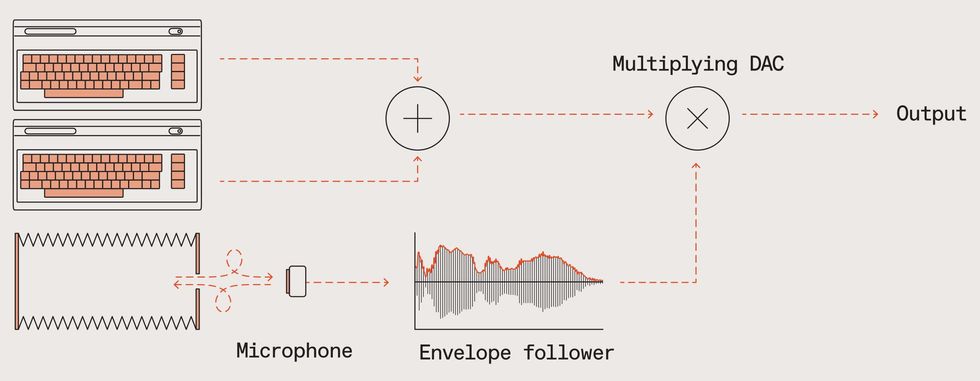

A real accordion uses the bellows to push air over reeds to make them vibrate. How fast the bellows is pumped determines the accordion’s loudness. So I needed a way to sense how fast air was being squeezed out of my floppy-disk bellows as I played.

This was trickier than I had anticipated. I went through several failed designs including one inspired by the “hot wire” sensors used in fuel injection systems. Then one day, I was watching a video and I realized that a person in the video was shouting in order to overcome noise caused by wind hitting his microphone. That was the breakthrough I needed! The solution turned out to be a small microphone, mounted at an angle just outside a small hole in the bellows.

Air flowing into or out of the hole passes over the microphone, and the resulting turbulence turns into audio noise. The intensity of the noise is measured, in my case by an ATmega8 microcontroller, and is used to determine the output volume of the instrument.

The bellows is attached to a simple frame built from wood and acrylic, which also holds the C64s as well as three boards with supporting electronics. One of these is a power hub that takes in 5 and 12 volts of DC electricity from two household-power adapters and distributes it to the various components. For ergonomic reasons, rather than using the normal socket on the C64s right-hand sides, I fed power into the C64s by wires passed through the case and directly soldered to the motherboards.

A second board emulates Commodore’s datasette tape recorder. This stores the Qwertuoso program. Once the C64s are turned on, a keyboard shortcut built into the original OS directs the computer to load from tape. The final board contains the microcontroller monitoring the bellows’ microphone and mixers that combine the analog sound generated by each C64s 6581 SID audio chip and adjusts the volume as per the bellows air sensor. The audio signal is then passed to an external amplified loudspeaker to produce sound.

In order to reach the keys on the left-hand side when the bellows is extended, my hand needs to bend quite far around the edge of what I dubbed the Commodordion. This puts a lot of strain on the hand, wrist, and arm. Partly for this reason, I developed a sequencer for the left-hand-side machine, whereby I can program a simple beat or pattern and have it repeat automatically. With this, I only have to press keys on the left-hand side occasionally, to switch chords.

The Commodordionwww.youtube.com

As a musician, I have to take ergonomics seriously. When you learn to play a piece of music, you practice the same motions over and over for hours. If those motions cause strain you can easily ruin your body. So, unfortunately, I have to restrict myself to playing the Commodordion only occasionally, and only play very simple parts with the left hand.

On the other hand, the right-hand side feels absolutely fine, and that’s very encouraging: I’ll use that as a starting point as I continue to explore the design space of instruments made from old computers. In that light, the Commodordion wasn’t the final goal after all, but an important piece of scaffolding for my next creative endeavor.

In this presentation we will build the case for component-based requirements management

This is a sponsored article brought to you by 321 Gang.

To fully support Requirements Management (RM) best practices, a tool needs to support traceability, versioning, reuse, and Product Line Engineering (PLE). This is especially true when designing large complex systems or systems that follow standards and regulations. Most modern requirement tools do a decent job of capturing requirements and related metadata. Some tools also support rudimentary mechanisms for baselining and traceability capabilities (“linking” requirements). The earlier versions of IBM DOORS Next supported a rich configurable traceability and even a rudimentary form of reuse. DOORS Next became a complete solution for managing requirements a few years ago when IBM invented and implemented Global Configuration Management (GCM) as part of its Engineering Lifecycle Management (ELM, formerly known as Collaborative Lifecycle Management or simply CLM) suite of integrated tools. On the surface, it seems that GCM just provides versioning capability, but it is so much more than that. GCM arms product/system development organizations with support for advanced requirement reuse, traceability that supports versioning, release management and variant management. It is also possible to manage collections of related Application Lifecycle Management (ALM) and Systems Engineering artifacts in a single configuration.

Global Configuration Management – The Game Changer for Requirements Management

In this presentation we will build the case for component-based requirements management, illustrate Global Configuration Management concepts, and focus on various Component Usage Patterns within the context of GCM 7.0.2 and IBM’s Engineering Lifecycle (ELM) suite of tools.

Watch on-demand webinar now →

Before GCM, Project Areas were the only containers available for organizing data. Project Areas could support only one stream of development. Enabling application local Configuration Management (CM) and GCM allows for the use of Components. Components are contained within Project Areas and provide more granular containers for organizing artifacts and new configuration management constructs; streams, baselines, and change sets at the local and global levels. Components can be used to organize requirements either functionally, logically, physically, or using some combination of the three. A stream identifies the latest version of a modifiable configuration of every artifact housed in a component. The stream automatically updates the configuration as new versions of artifacts are created in the context of the stream. The multiple stream capability in components equips teams the tools needed to seamlessly manage multiple releases or variants within a single component.

GCM arms product/system development organizations with support for advanced requirement reuse, traceability that supports versioning, release management, and variant management.

Prior to GCM support, the associations between Project Areas would enable traceability between single version of ALM artifacts. With GCM, virtual networks of components can be constructed allowing for traceability between artifacts across components – between requirements components and between artifacts across other ALM domains (software, change management, testing, modeling, product parts, etc.).

321 Gang has defined common usage patterns for working with components and their streams. These patterns include Variant Development, Parallel Release Management, Simple Single Stream Development, and others. The GCM capability for virtual networks and the use of some of these patterns provide a foundation to support PLE.

The 321 Gang has put together a short webinar also titled Global Configuration Management: A Game Changer for Requirements Management, that expands on the topics discussed here. During the webinar we build a case for component-based requirements management, illustrate Global Configuration Management concepts, and introduce common GCM usage patterns using ELM suite of tools. Watch this on-demand webinar now.